Adhering to your personal values when selecting

investments that you want to support or avoid is common. You may choose to skip

investing in companies that provide sins, vices, or conflict with your personal

values. For example, your list of stocks to avoid may be businesses involved

with alcohol, cigarettes, gambling, marijuana, opioids, military defense, and

pornography. There are many ways to screen companies; you could select stocks

with only U.S. manufacturers or avoid products made or sold in a country run by

oppressive governments like Cuba, Venezuela, or North Korea.

Investment funds and advisors seeking to market to

investors’ tastes create mutual funds, ETFs, and lists that correspond with

these criteria for easier investing. A big problem arises when these investing

criteria move beyond the obvious toward popular but fuzzy terms such as rating

a business’s sustainability, environmental impact, social justice, diversity, consumer

privacy, engagement, green, inclusivity, responsibility, ethics, human rights,

faith-based, corporate governance, etc. These terms are so subjective that you

must ask the person using them exactly what they mean. And remember, these

definitions change over time. The result of this confusion is that companies

are being unjustly rewarded and punished with inaccurate labels by investment

funds and advisors.

*Note, some of the common vernacular today is “ESG,” an

acronym for environment, social, and governance criteria for investing; “SRI”

for social responsible impact; “DI” for diversity and inclusion; and “CSR” for

corporate social responsibility. While many institutions claim they have

‘vigorous and in-depth methodologies’ for scoring their ESG labels, the

briefest glance at them reveals this is not at all true. Try to find the exact

details on how they actually evaluate a specific criterion for a company:

https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/123a2b2b-1395-4aa2-a121-ea14de6d708a

Some of the issues leading to erroneous ratings and

investing conclusions from these ill-defined ESG terms occur because you are entering

into the endless stormfront of:

- Conflicting study results

- Not evaluating all of the cradle-to-grave

elements to a solution

- Promoting several types of unfairness to reduce

one type of potential unfairness

- Failure to consider side effects and secondary /

tertiary consequences

- Political correctness hypocrisy

- Subjective and biased trade-offs that are assumed,

not reviewed

- Junk science and mistaking correlation with

causation

- Popular misconceptions, fallacies, and error

propagation

- Requiring failed socialist precepts in governing

policies

- Wind/solar manufacturing and intermittency is usually

solved with fossil-fuel energy

- Poor behavior as one-time events vs. ongoing

part of company culture

- Demanding corporate policy changes for manufactured

problems that do not exist

- Judgments with incomplete information

- Utilizing plastic vs. its alternatives that have

a +400% higher carbon footprint

- Unsettled science with conclusions that have

been flip-flopping

- Falsified data, fake allegations, and debunked

assertions

- Confusing efficiency with sustainability

- No reporting data or visibility to actual

behaviors that matter

- Financial sustainability is sometimes just financially

unaffordable welfare

- Political propaganda overriding factual details

- Mandating product improvements that physically

do not exist

- Plus numerous other issues (for brevity, I

deleted over 20 additional points)

A certification example that highlights just a few of

these problems is LEED certification (leadership in energy and environmental

design). In the early 1990’s, the National Resource Defense Council developed LEED

construction standards for buildings that reduce their environmental impact

over regular construction. This became an international standard and popular for

businesses to highlight their green commitment. Many governments provide tax

credits only for LEED certified buildings. However, there is a long list of

criticisms about LEED certified buildings, including energy and water usage being

poorer than regular construction. For every architect that thinks LEED is on

the cutting edge of progress, there are architects who claim: it requires inappropriate

materials, does not respond to changes in technology, increases the cost and

energy to build more than any efficiency can recover, suppliers may have bribed

their way onto the approved list, that LEED has devolved into a scam to sell

fake PR (called greenwash) to grab millions in tax credits. Some call LEED a

taxpayer-funded fraud that worsens environmental impact – the opposite of the

one item it was supposed to improve. There are similar criticisms for

supply-chain certifications such as “Fair trade,” “Conflict Free,” “Biodegradable,”

and even “Organic.”

When simply planting trees to “help the environment” is

rife with reverse side-effects that overwhelm any benefits, critics of ESG

labels claim that it is just the latest snake-oil in “Virtue Signaling” marketing

by opportunists to the gullible. In a recent Youtube video, the founder of a

large ESG financial advisory firm vilified an industry as being inherently

unethical, and included any supplier related the industry. He published this

without citations, evidence, or confirmation – just inflammatory remarks from

some professional victims. Yet, with a single mouse click, I found

contradictory evidence and the logical explanation for one of his “unethical

outrages” he used to publicly malign an innocent industry.

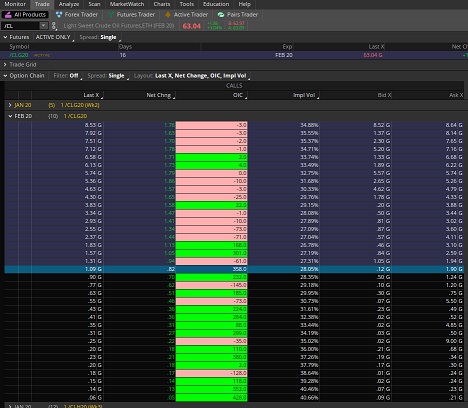

ESG has caught the attention of the U.S. Securities and

Exchange Commission. It is now investigating whether ESG Investment Funds are

making false claims by looking into the criteria and methodology for rating a

company for ESG. One SEC commissioner, Ms. Hester Peirce, says, “ESG has no

enforceable or common meaning. They are relying upon research that is far from

settled… We should be wary of a self-appointed crowd pinning a Scarlet Letter

on a business for fun and profit.” This is not surprising because no company

gets the same ESG rating by any ESG advisors.

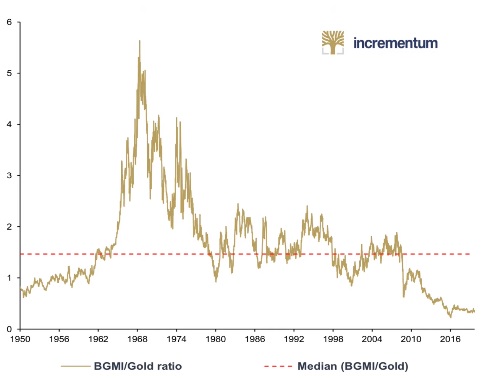

Why are you investing at all? Likely to reach your financial goals – so you want to place money with the highest likelihood for it to become more valuable over time. Bloomberg did a 7-year backtest among the S&P 100 stocks. They compared the highest rated ESG stocks compared to the non-compliant ESG stocks and the result was the non-compliant stocks performed 50% better than the companies deemed “virtuous.” (Of course, there are other studies performed by ESG firms, with a clear conflict of interest, that make the opposite claim). Expressing your personal values in your investments can be important, and as an investor, you will likely come across ESG marketing materials from investment brokers and advisors. In my opinion, you should never allow anyone else to stamp a company for you with vague and possibly incorrect labels.